Fluid theraphy SQ

![]() Wait a few seconds for the videos to load

Wait a few seconds for the videos to load

FLUID THERAPY……a life-saving treatmentDosage: 5% body weighInfusion: 80% LRS (Lactated Ringer`s Solution) + 20% Duphalyte®Administration: subcutaneously (SQ) in the inguinal crease—–Patients should be warmed before administering fluids—–An animal’s body is made up of a great deal of fluid, which, in an adult, can mean that 50–60% of the body is water. Younger Animals will have higher water content, about 70–80%, whereas older animals have reduced body water, about 50–55%. Also, fat contains less water than other types of tissue so consequently fat animals will have proportionally less water. Two-thirds of a body’s water (equivalent to 40% of body weight) will be inside the cells of the body tissues. This is known as intracellular fluid (ICF). The remaining one-third (equivalent to 20% of body weight) will be outside the cells and is called extracellular fluid (ECF). The ECF is further divided into: (1)- 5% plasma water which is contained within the blood vessels. (2)- 15% interstitial fluid which is contained in the spaces between the cells. (3)- Less than 1% trans-cellular fluid for the processes like gastrointestinal secretions and cerebrospinal fluid. The body constantly loses water from the ECF. This inevitable water loss is essential to support the four functions from which the loss emanates: 1- Respiration. From the respiratory tract during breathing, since expired air is moistened as it passes through the nasal passages and the respiratory system. 2 – Urination. From the kidneys during urination, although the body’s metabolism will adjust for changes in hydration and water availability for excretion.3 – Gastrointestinal processes. From the gastrointestinal tract in the faeces or serious fluid losses through diarrhoea or vomiting.4 – Skin losses. Reliant on ambient conditions, fluids are lost through the skin or from pores in the feet during perspiration. Birds will open their mouths to disperse heat by vibrating the gular region in their throats. To replace this water loss, an animal, on average, must take in about 50 ml/kg of water per day. Smaller animals, especially birds, may have a greater water requirement than this, i.e. a range of 66–132 ml/kg per day, the smallest needing the most pro rata to body size. Drinking is obviously the best way of getting water, but some birds and other animals very rarely drink. Their water intake is gained from their food whether it is meat, vegetable matter, or, as some finches manage, the metabolism of dried seeds and nuts for their water content. DEHYDRATION Commensurate with its size, any animal will survive going without food for far longer than it will survive without fluid intake. An animal that does not manage to eat or drink for any length of time will still be losing fluid at the rate of about 50 ml/kg per day. Although as dehydration sets in the kidneys will concentrate the urine to reduce water loss, losses from respiration, the skin and gastrointestinal tract cannot be reduced. Therefore a reduced water intake can easily become life threatening to an animal, as can increased fluid loss such as through serious diarrhoea or vomiting. Described simply as a fluid deficit percentage of bodyweight, a 15–25% deficit can generally be taken as fatally irretrievable.Many wildlife casualties, especially orphans, will be showing some degree of dehydration. This is just because they will not have eaten or drunk for a period of time and may have been lying unprotected from hot summer weather. In fact any wild bird taken into care can be assumed to be 5% dehydrated. Unless the dehydration is very pronounced, 10–15%, the condition may not be life threatening. However, the added stress of being brought into captivity and handled may well push the casualty to its limits. Whatever the degree of dehydration it is absolutely crucial that the casualty is given the right fluids without any delay. Too much fluid, especially parenterally, can cause pulmonary oedema in some species, while too little will not remedy the situation. The protocol is to try to replace the deficit over 2–3 days while still providing daily maintenance for those days.From: Practical Wildlife Care, Second Edition, Les Stocker MBE

Gepostet von Falciot Vencejo Swift Rehabilitation am Sonntag, 5. Juli 2015

FLUID THERAPY SUBCUTANEOUS ADMINISTRATION SQ Video 2 of 2

Gepostet von Falciot Vencejo Swift Rehabilitation am Sonntag, 28. Juni 2015

FLUID THERAPY SUBCUTANEOUS ADMINISTRATION SQ Video 1 of 2

Gepostet von Falciot Vencejo Swift Rehabilitation am Sonntag, 28. Juni 2015

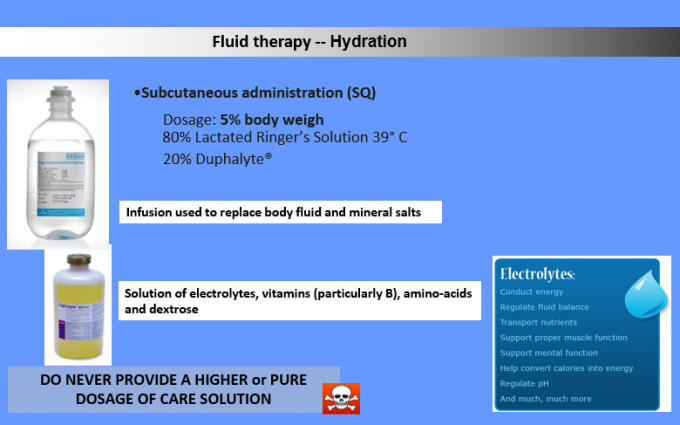

FLUID THERAPY, a life-saving treatment

Dosage: 5% body weigh

Infusion: 80% LRS (Lactated Ringer`s Solution) + 20% Duphalyte®

Administration: subcutaneously (SQ) in the inguinal crease (, into the loose skin of the upper inner thigh and abdomen)

—–Patients should be warmed before administering fluids—–

An animal’s body is made up of a great deal of fluid, which, in an adult, can mean that 50–60% of the body is water. Younger Animals will have higher water content, about 70–80%, whereas older animals have reduced body water, about 50–55%. Also, fat contains less water than other types of tissue so consequently fat animals will have proportionally less water. Two-thirds of a body’s water (equivalent to 40% of body weight) will be inside the cells of the body tissues. This is known as intra-cellular fluid (ICF). The remaining one-third (equivalent to 20% of body weight) will be outside the cells and is called extracellular fluid (ECF).

The ECF is further divided into:

-5% plasma water which is contained within the blood vessels.

-15% interstitial fluid which is contained in the spaces between the cells.

-Less than 1% trans-cellular fluid for the processes like gastrointestinal secretions and cerebrospinal fluid. The body constantly loses water from the ECF.

This inevitable water loss is essential to support the four functions from which the loss emanates:

1- Respiration. From the respiratory tract during breathing, since expired air is moistened as it passes through the nasal passages and the respiratory system.

2 – Urination. From the kidneys during urination, although the body’s metabolism will adjust for changes in hydration and water availability for excretion.

3 – Gastrointestinal processes. From the gastrointestinal tract in the faeces or serious fluid losses through diarrhoea or vomiting.

4 – Skin losses. Reliant on ambient conditions, fluids are lost through the skin or from pores in the feet during perspiration. Birds will open their mouths to disperse heat by vibrating the gular region in their throats. To replace this water loss, an animal, on average, must take in about 50 ml/kg of water per day.

Smaller animals, especially birds, may have a greater water requirement than this, i.e. a range of 66–132 ml/kg per day, the smallest needing the most pro-rata to body size. Drinking is obviously the best way of getting water, but some birds and other animals very rarely drink. Their water intake is gained from their food whether it is meat, vegetable matter, or, as some finches manage, the metabolism of dried seeds and nuts for their water content.

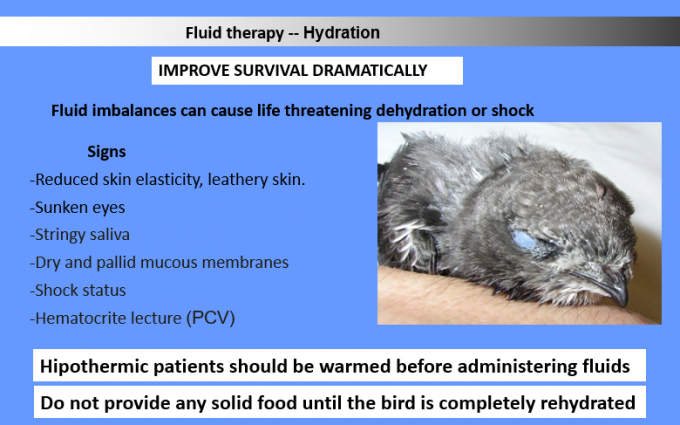

DEHYDRATION

Commensurate with its size, any animal will survive going without food for far longer than it will survive without fluid intake. An animal that does not manage to eat or drink for any length of time will still be losing fluid at the rate of about 50 ml/kg per day. Although as dehydration sets in the kidneys will concentrate the urine to reduce water loss, losses from respiration, the skin and gastrointestinal tract cannot be reduced. Therefore a reduced water intake can easily become life threatening to an animal, as can increased fluid loss such as through serious diarrhea or vomiting. Described simply as a fluid deficit percentage of body weight, a 15–25% deficit can generally be taken as fatally irretrievable.

Many wildlife casualties, especially orphans, will be showing some degree of dehydration. This is just because they will not have eaten or drunk for a period of time and may have been lying unprotected from hot summer weather. In fact any wild bird taken into care can be assumed to be 5% dehydrated. Unless the dehydration is very pronounced, 10–15%, the condition may not be life threatening. However, the added stress of being brought into captivity and handled may well push the casualty to its limits.

Whatever the degree of dehydration it is absolutely crucial that the casualty is given the right fluids without any delay. Too much fluid, especially parenterally, can cause pulmonary oedema in some species, while too little will not remedy the situation.

The protocol is to try to replace the deficit over 2–3 days while still providing daily maintenance for those days.

From: Practical Wildlife Care, Second Edition, Les Stocker MBE